Content is the key to understanding the works of Qin Qi. The artist himself has said that the content and themes he wishes to express guide the expressive techniques he employs. This explanation is connected to several different questions: why he is interested in these themes, how these themes relate to his expressive techniques, and how he understands and presents the language and forms of painting. These questions lay the path for entering into his rich, ever-changing oeuvre. Though Qin Qi has always been deeply engaged in the research of technique and form, something about his inherent nature has led him to never place great importance on the language of painting. His focus is more on what he can express through the painted image, even if such things are overly individual and difficult for the viewer to grasp or describe. Using the methods of painting, he has created an experiential world akin to that of a child, mimicking the alluring, good-willed, romantic or awkward situations in everyday life and the imagination, the people around him all appearing “interesting.” Meanwhile, Qin Qi is also an artist who is able to employ the language of painting with high levels of precision and power, using his grasp of the basic elements of painting, as well as novel approaches to them, to present us with his imaginings. Drawing on past experience allows the viewer easier ingress into his works, so Qin Qi often places the compositional linguistic elements at the fore, or at least treats them as equal in importance to the content.

Qin Qi is one of many artists born in the 1970s and trained at one of the big eight art academies. This generation’s youth coincided with China’s era of reform and opening. He grew up in Shaanxi, deep in China’s interior, where the slow and steady pace of social life that marked the past still continues in some form today. There, the value of the individual gradually expanded, but the new external cultural resources were still scarce and somewhat confused. Lacking a strong family background, this youth was more susceptible to the influence of mass culture, with films such as Shaolin Temple, radio plays such as Legend of Yue Fei, Yang Family Generals and Romance of the Three Kingdoms and TV dramas from Japan and Hong Kong coming to subtly influence this young man. Unlike the more developed cities of the eastern seaboard, foreign influences were mainly limited here to the mass broadcast media. Changes in customs and culture, particularly novel popular culture influences, were markedly behind in the interior compared to cities such as Guangzhou and Shanghai that had led the way in liberalization. As a student and a growing youth, Qin Qi was the kind who sought independence early on and matured quickly. Honest, forthright and tenacious, Qin Qi’s values came to quickly focus on clear, simple and vivid things. We can see that the formation of Qin Qi’s values system was destined to be linked to influences from tradition and folk culture.

The education and values of China’s art academies are rooted in the Western system and revolutionary traditions, particularly in the oil painting departments. Modelling, colors, representation and abstraction, realism and expression, subjective and objective expression, form and pattern, these systems were maintained and changed through the demands and training of the students at the academy. The academy experience stretching from art academy middle school to postgraduate studies is one that Qin Qi shares with many contemporary artists. In the constant training and testing, and on to his own teaching, he had to find ways to balance his personality and his early-maturing values to adapt to this system. Under constant demands to perform as a good student and good teacher, Qin Qi came to demand the same from himself. Despite this, personal elements from beyond the academy, including his early-formed preferences, would emerge in profound ways throughout every stage of his artistic career.

A partial assessment of the subject matter in Qin Qi’s artworks shows a particular concentration in a few areas: animals, particularly horses, cranes, beasts and geese. The animals expand into sculptures of animals, as well as fruits, foods in the kitchen, utensils, and Baroque renderings of kitchens and taverns a la Caravaggio and Velazquez. There are also people, mostly his friends, as well as people with clear occupational identities, such as Lamas, chefs and athletes. There are scenes, such as religious temples, Western border regions and exotic locales. These themes are mainly derived from Qin Qi’s innocent curiosity, his everyday life, and things he believes can be turned into artworks through his individual approach to painting. The opposite approach is quite commonplace among Chinese artists: starting out from the changing times, seeking out markers of individual style or unique properties of the medium, approaching the construction and deconstruction of the art system, etc. After Qin Qi’s individual look took shape in 2006, he began to establish distance from these ill-fitting methods in his selection of subject matter.

From 2002, when Qin Qi completed his graduate studies in oil painting at the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts and began teaching at the academy, until 2005, Qin Qi experimented with various different methods. He selected various scenes from society, everyday life and his own experiences that were extreme or inexplicable, beginning with a loose and fluid snapshot rendering and eventually shifting into detailed depictions with the unified tones and atmosphere of photography. Another component of his works was the direct transfer of handwritten notes and passport photos into paintings. Overall, this period showed a young artist making pure responses to life and art, seeking out his own place somewhere in the tense standoff between image and painting. Looking back over his works from this period, we can see a few shadows of Qin Qi’s current artistic methods, such as the Baroque rendering of the complex, distorted folds of clothing.

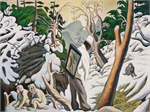

In 2006, beginning with the large format works Captain, Clumsy Pine Crane and Yang Jie, Qin Qi began to settle into a stable relationship between thematic content and painting language. Continuing with the brushwork and paint texture of previous works such as Target and Danger!Do Not Approach, as well as the correspondence between the placement of objects and the observer, Qin Qi used heavy yet freewheeling brushwork and colors to present his individual style. Aside from several Western China-themed works, the artist did not produce many figure paintings in this period, focusing instead on landscapes and still lifes, as seen in Tibetan Zoo. The extremely thick paints make the colors composing the forms to appear with the compact arrangements of inlaying, an approach that markedly differs from conventional color mixing, linking Qin Qi indirectly to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. This phase continued until 2009 with slight adjustments, the brushstrokes tending towards increased order and the compositions growing increasingly steady, as seen in Untitled (Indoor). In this period, Qin Qi’s works reached a level of initial maturity. The deep impression left by his expressive methods often served to conceal the artist’s original interest in the content. From a certain perspective, Qin Qi’s embrace of material and instinct that produced a sense of living weight, and his attitude placing experience over criticism, were all within the realm of his individual experience.

In 2012, Qin Qi entered into a new phase, and though it has only lasted for two years thus far, this shift has proved to be of critical importance. As a curtain call and transition from the previous phase, Qin Qi began by painting a series of landscapes in outline, gradually increasing simplicity in order to simplify forms while also incorporating his preference for strong contrasts over transitions and bringing in elements of Cubism. Qin Qi sees Cubism as still being part of classicalism, the last time in art history that effort was still expended towards modelling. His importation of these elements was in order to serve the needs of his expression. At this time, his interests in subject matter returned to figure portraits and scenic elements with romantic overtones. This includes the exotic, tropical scenes he had encountered in his travels, which he created using methods that were “new to him.” For a painter who had already formed a unique appearance, it is quite rare and precious to make a natural, proactive transition to a new appearance, and quite risky as well, demonstrating that artist’s character and his understanding of art. Out of his sense of the importance of painting style, Qin Qi incorporated elements of Cubism and Symbolism in his expressions in an attempt to avoid the isolation caused by the fleeting nature of individual talent and character. If the old Qin Qi used the deconstruction of the world to construct the self, he has now transitioned into a realm of constructing the world in order to deconstruct the self. Of course, construction and deconstruction are mutually interchangeable, and are themselves shifting paths.