In the early twentieth century, in the writings of Clement Greenberg, the secular, narrative and realistic forms of academy art represented kitsch culture, while the dismantlement and rebellion against the academy formed a major wellspring for abstract or avant-garde art. After this, just as the so called readymade “ended” painting, acts of provocation and resistance against the academy system, and even how to escape the logic of contemporary art, became a model for a form of avant-garde or contemporary practice. If there still existed an ambiguous relationship between Chinese avant-garde art and the academy system in the 1980s, then since the 1990s, particularly in the field of painting, the two grew increasingly divided and tense. This still stands today as the most widely accepted mainstream narrative of Chinese contemporary art.

Reality, however, is not so simple. In recent years, the rethinking and appraisal of contemporary painting has unfolded atop a foundation of the art history dimension, and the knowledge and experience of art history has been intertwined with the academy system. In fact, as early as the mid-1990s, such figures as Wang Xingwei and Wang Yin were already engaging in rethinking within the art history dimension, even if their practices were not directly connected to the academy system. Later, however, this trend has grown increasingly apparent with young artists such as Qin Qi, Qiu Xiaofei, Gong Jian and Li Qing. Qin Qi has remained on the faculty at the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts since his graduation in 2002, and crucially, his creations have always pressed forward within this system. Of course, looking today, the majority of contemporary artists to emerge since the 1990s have come from the academies, and just like the American avant-garde of the time, their practices have mainly employed methods and goals aimed at escaping this system, opposing painting and even escaping the art history system. Meanwhile, other artists have maintained an unclear connection with the academy system, always oscillating between the two. Unlike the abovementioned examples, Qin Qi has not opposed painting itself, nor has he attempted to extract himself from the systems of art and art history, let alone find a hybrid state or balance between academy and anti-academy. His practice presents the way in which he uses painting methods to reflect on painting, to break free of the fetters of art history from within art history, and to use conceptual methods to suspend conception. This thread of inner tension runs through the years of his work, coming to form a conscious, sustained momentum.

To be frank, there is no way to summarize or define Qin Qi’s painting. Not only would a definition squeeze or simplify this artist’s rich practice, the multifaceted nature of his practice makes it impossible for us to comprehensively sort out his overall artistic appearance. Nevertheless, in the past few years, he has undergone several distinct changes. The aim of this essay is not to categorize him or bestow him with a particular significance but to provide a new perspective and path for entering into his painting as well as its rhetorical shifts.

Touch, Vision and a Constellation of Subjects

Historically, Rembrandt was probably the first painter to be conscious of the texture of paint and brushstrokes. He used a large amount of thick strokes, sometimes using a spatula or finger in place of the brush to apply paint in order to heighten the sense of volume and visual richness. This method of applying paint is, in a formal sense, rooted in the needs of modelling. Heinrich Wölfflin believed that this was for pure visual appearance, and that the lines and outlines of Albrecht Dürer, and the material essence he sought, had given way to touch. That is to say, the distinction between Rembrandt and Dürer on this level was the distinction between vision and touch. But later, the new art historian Svetlana Alpers saw it as exactly the opposite. She believes that Rembrandt used paint to cover over this world, shifting our focus from the subject of the painting to painting itself. Here, paint is no longer just a visual medium but summons our sense of touch as well. It is this latter function that touched off a new means of perception. Like Descartes’s “seeing with the hand,” he used touch to replace sight and vision. That is to say, Rembrandt led people’s sights to the act of seeing, rather than the principles of image production. Two hundred years later, Édouard Manet’s singular painting technique may have been chiefly inspired by Frans Hals, but Rembrandt’s awareness of the substance of paint still had an indirect influence. It was the lack of materiality that led to the negative spatial relationships in Manet’s paintings. Georges Seurat was clearly the most absolute in terms of making paint self-sufficient. Though it was in the service of modelling, since it was entirely rooted in rational scientific calculations, it did away with the hands and the eyes to the point that Thierry de Duve views his art as a readymade practice preceding that of Marcel Duchamp. By the time of Greenberg, the self-sufficiency and purity of paint as a medium had become one of the elements composing formalism.

One could say that into the 20th century, medium was completely liberated. Painters were no longer as careful and “reverent” towards paint, brushstrokes and painting as Rembrandt and Seurat. The world of painting has been flooded with free, diverse, even “violent” practices. The the reason I have expended so much ink in capturing this thread of art history is to demonstrate that Qin Qi’s practice has been built within the connections of art history in order to seek out possibilities in form, rather than merely doing as he pleases “after the end of art history.” Of course, Qin Qi’s thick paint applications are not rooted in Rembrandt and Manet, nor are they under the influence of Seurat and formalism. They do, however, share the same awareness of paint, touch and texture. To be more precise, his practice is rooted in his steeping in the longstanding realist traditions (including classicalism) of the Chinese academy education, and thus, Qin Qi’s paint and brushstrokes are not self-sufficient, and the medium-nature of his painting is not pure. As stated above, however, Qin Qi has not consciously chosen to place himself outside of the system, but is magnifying the mass of the paint on the level of brushstrokes, and altering the narrative structure of the image in an attempt to escape the deep-rooted realist tradition.

The graphic base of Qin Qi’s pictures clearly strays from realism, but it appears that his interest is more on the techniques of modeling. Here, the thickness of the paint and the haphazardness of the brushstrokes are like experiments in modeling techniques, used to alter the base of the image. This alteration is not merely to bring out texture and materiality, and thus reconstruct a flat graphical narrative, but also to use the expansion and contraction of space to explore the mechanism of viewing. Thus, the paint and brushstroke do not so much serve to construct image and form as they are interfering with it. In other words, the sense of touch is dismantling the sense of sight. In the 2004 work Hello 2, aside from the relational structure between paint/brushstroke and image, a new layer of vocabulary/text interference has emerged within the painting. Perhaps due to the excess complexity of these two structures, they end up cancelling each other out. In later works such as Panda (2006), South Lake (2007), Belt (2008) and the Three Backboards series (2008-2009), he removed the latter layer of relationships, purifying and magnifying the relationship of tension between touch and vision, using the methods of touch to dissolve the gaze.

The hypothesizing of the gaze does not imply that painting itself is just viewing, or that it is a subject or object controlled by the viewer’s gaze. Qin Qi is also declaring the subjectivity of painting. Whether it is the unaltered, original base, or the “secondhand image” that he has rearranged to take on surreal tones, through the translation of brushstrokes and paint, they all lead to the understanding and recognition of the objects in the painting. Most of the time, the “base” of his images is experiential, and concrete at that. We can see in The Tortoise (2006) and the Turnip series (2007) that he has intentionally extracted the background of objects, or parts of them that he sees as superfluous, leaving only the object upon which his attention is focused, or leaving only materialized paint and brushstrokes, while his “meticulous” depiction of color and structural relationships maintain a unified, stable undertone for the painting, but this unity appears quite “uncoordinated” with the apparently “chaotic” brushstrokes. As I see it, this aspect is releasing the subjectivity of painting itself, while also attempting to restore the subjectivity of the objects, thus canceling out its original recognizable and social attributes. This phenomenological extraction and restoration seems to be a return to the object itself, but the practice itself is tacitly forcing the subject to yield for the artist. Thus, between the object, paint/brushstrokes, painting and the artist, there forms a constellational subject framework.

Image, Form and the Weight of the Picture

The fact is that Qin Qi’s selection of a graphical base is not just the extraction of a specific concrete object. It is more often the case that he is weaving the setting for a grand narrative.

If, in the still life paintings with their relatively simple compositions, or in similar artworks, touch and vision form mutual interference, then in the graphic narratives of the larger scenes, the energy of brushstrokes and paint is doubtless limited. Qin Qi’s selection of graphic bases is extemporaneous, and in the painting process, he often engages in the necessary collage, cutting, alteration and editing to finally form a surreal scene that differs from the original base. The six-part painting Captain from 2006 is perhaps his most discussed work. From the relationship between graphical motifs to the arrangement of spatial structure, Qin Qi seems to be producing an “enigma” or state of “suspense.” Even now, I still do not know the story behind this painting, nor can I confirm whether the motifs of plaster bust, police car, canoe and others are some kind of conceptual allegory, but the deep grey tone, geometric spatial construct and absurd narrative come together to create an atmosphere of repression. At this time, the strength of the brushstrokes and the thickness of the paint are not enough to constitute interference. To the contrary, they serve to enhance the visual sense of repression in the painting, heightening the weight of the painting, using a rejection method to establish a relationship with the gaze of the viewer.

Evidently, Captain also possesses a visual structure of depth. In Everlasting Pool (2005) and The Reptiles Museum (2007), Qin Qi did not follow with this spatial relationship, instead employing a bird’s-eye view or an “unfolding” space, using the vertical relationship between painting and gaze to cancel out or close off the visual structure of depth. This closing-off is of course still a form of graphic narrative, but its connection to brushstrokes and paint is now different from what it was in Captain. Here, the thickness of the paint and the strength of the brushstrokes are themselves closing off the space. Though it is releasing the visual sense of repression, it no longer stems from the spatial structure. Instead, it is a sense of repression rooted in flat compositions and the materiality of the brushstrokes. At this point, the image, its inner structural relationships and its narrative logic form the center of the painting. In his recent works, however, we discover that Qin Qi has shifted the focus from the visual organization of the image to the sculpting of the form.

The painted picture is still constructed atop a graphic base, but it apparently no longer constructs fabricated narrative, instead intentionally magnifying the forms and structures of the people and objects in the picture. The graphic bases are mostly derived from photographs of everyday life as well as images of folkways and customs. Unlike before, he has no longer obscured the relationships between background, people and objects, but has instead strengthened the boundaries between them. Much of the time, he has not altered the color tone of the graphic base, but used brushstrokes on the original foundation to clarify the structure, volume and relationships between each element. Of course, it is not a realist re-creation of the image. For instance, in Violin Player (2013), Xing Jie (2014) and the Xiao Guang series (2014), he used distortion (for example stretching the bodies or certain parts of his figures) to exaggerate the shapes of the figures. This exaggeration is not an embodiment of taste but an experiment in the shifting of structure to seek out the possibility for the expansion of vision space within the threads of art history.

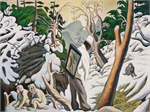

The 2014 works Tropical Scenery, Blue Umbrella, White Sand, Huilan’s Geese and Adult and Baby Elephants are derived from his sights and experiences on recent travels. Correspondingly, Theodore Rousseau’s Barbizon techniques and Paul Gauguin’s symbolism naturally form the base tone of the painting. Here, however, his original level of brushstrokes has been highly compressed, highlighting only the volume, blocking and structural relationships of the forms. In the details, he has employed to a certain extent the Cubist techniques of Fernand Léger and Pablo Picasso, transforming them into a sense of primitive woodcutting and carving, while the pathological appearance of the people and things seems to bear the marks of Frida Kahlo. As a result, the overall pictures appear loose and free, but the hard-edged structures and blocks share very taught relationships. Interestingly, almost all of the art history influences listed above were very concerned with growth. Whether it is nature, life, shapes or even painting itself, I believe that Qin Qi’s choices are not entirely unconscious. Perhaps his focus is on this growth itself. Thus, what is becoming self-sufficient is not the brushstroke but the shape structures that can bring the possibility of growth to within the painting. As I see it, this approach to shaping is not a declaration of the internal unity of the painted picture, but the use of blocks and bodies as structural relationships that dismantle the picture. This aspect is more evident in his new Lama series (2014), which not only clearly defines the boundaries between structures and blocks, but also further dismantles the picture through the purification and division of colors. This division is not mechanical but dynamic, even wild.

Unlike the previous graphic narratives, the center of the picture here is no longer manifest in a visual sense of repression, but generated instead spontaneously by the structure of the shapes.

Experience, Knowledge and the Suspension of Concepts

Qin Qi’s practice is doubtless still rooted in a form of experiential awareness. Here, experience includes body/society, gaze and knowledge. Since 2004, Qin Qi’s work has unfolded within these multiple, intertwined forms of experience. We cannot deny that the thickness of paint, the strength of the brushstrokes and the weight of the picture are connected internally to the painter’s bodily and social experiences, and we also cannot deny the way in which the experience of the gaze influences the painter’s construction of his own visual mechanism. We especially cannot deny that in this process, knowledge, particularly the understanding of art history, is pushing him to experiment and explore the viability of painting. But like most artists, as he has grown older, the body’s perceptions have been gradually absorbed and depleted by the rational knowledge and gaze, and so his consciousness and experimentation in form is, as I see it, not bodily but intellectual. Recent works such as Tropical Scenery (as well as the Lama series) bridge the divide between the multiple experiences of the body, knowledge and the gaze. This change suddenly took place around the year 2009. The Book series, created at the same time, was the deftest of allusions. From this point, he began gradually contracting depth, shifting towards a flat skin, and began to be more constrained. This is also the reason why I chose to approach his work through the dimension of art history.

Perhaps such an analysis along the dimension of art history seems to intentionally ignore Qin Qi’s conceptual side. Qin Qi does not predetermine any particular concepts, and has never voiced any clear attitudes. If he does have concepts, they are pressed out from his constructed visual mechanisms and experiments in the operations of the medium of painting. In other words, the concepts are suspended by others after the fact. This is particularly apparent in his recent works, where the complex relationships of paint/brushstrokes, touch/sight and image/form conceal any cultural or political metaphors that the picture may have contained. Of course, suspension does not imply the cancellation of concepts, but the construction of a new conceptual mechanism. At this time, the so called concept is actually the art historical significance, and the awareness and probing of the current art system by this conceptual mechanism, as well as the field of vision, perspective and method for recognizing the world that it can provide for us. We could even say that Qin Qi’s practice is one of intellectualizing art history and painting, and whether it is in regards to the current art system, or the cultural order of an era, this intellectual practice can lead to an invisible stance, with the visible being the apparent shifts of its cultural perceptions. When the city and industry shift to the folk and the everyday, when the “depth” of art is gradually replaced by the “skin” of perception, it is actually a metamorphosis of the subject. This metamorphosis, however, has not weakened the ferocity and animal spirit found throughout his work.

The art of the increasingly confident Qin Qi is still progressing, so we still cannot fully ascertain his significance to art history. But within the current art system, his practice has no lack of directedness. He at least stands out in this regard. Looking today, this directedness lies in the fact that not only does he pull us back into the art history dimension as he understands it, he also demonstrates how he has incorporated art history knowledge and experience with everyday body/gaze experiential methods to extricate himself from within the art system, including the aging academy system. He is not one to blindly declare positions. He can even be hesitant and indecisive, but his repeated trials and experiments have allowed him to release more intellect. This has not removed his own sentiments or body, and in fact, the necessary restraint has actually given more potency and weight to his painting. Here, I would like to use two new works from 2014, Monkey and Hooded Painter to formulate my conclusion. In my opinion, these two works are sufficient to explain the significance of his recent practice.

These are both paintings about painting. We can tentatively conclude that Qin Qi is using Rousseau methods to create a Rousseau painting scene, or that he is engaging in a practice of archaeologically excavating the painting of Rousseau, another means for reentering into art history. This is not just a knowledge method, but a knowledge method using the perceptions of the body. The two paintings both depict the setting in which the painter works, one being an outdoor life study, the other being an indoor still life. Coincidentally, these two settings are both fundamental educational methods of the academy system. But when he created these two works, Qin Qi was not using techniques from the standard teaching model but employing a linguistic method from outside the system. Here he is giving us hints about how he uses his own methods to extricate himself from this decrepit system. At this time, it must be reasserted that in this process, the construction of the subject has no conclusion, and that this is extrication itself.

[1] Clement Greenberg, Avant-Garde and Kitsch, collected in Art and Culture, translated by Shen Yubing, Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Publishing House, 2009, pp. 3-20.

[2] Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History, translated by Pan Yaochang, Peking University Press, 2011, pp. 48-108.

[3] Svetlana Alpers, Rembrandt’s Enterprise: The Studio and the Market, translated by Feng Baifan, Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Fine Art Publishing Group, 2009, pp. 21, 23 and 31.