Life Most Intense

'[Art's] deepest urge is to trap fugitive vision and passing sensation–elation, horror, meditative calm, desire, pathos–the feelings we have when we experience life most intensely, before routine, time and distance dull the shock and veil the memory. This craving to nail down transient experience is an unassuageable craving…'1

Ma Ke was born in Shandong [Zibo] in 1970. He followed the route typical to most oil painters in China who are the products of its art academies. He displayed a talent for drawing as a child, overcame some familial opposition to his desire to study art before triumphing at an academy. Ma Ke was accepted into the oil painting department of Tianjin Art Academy in 1990, where he completed a Bachelor’s degree. In 1993, the same year Ma Ke graduated, he was also one of the first recipients of the Luo Zhongli Scholarship which was established in 1992. As a reward for his skills, he was retained by the academy as a teacher, and he would likely have remained there in Tianjin were it not for an opportunity presented to him in 1998 that took him abroad to Africa as as volunteer teacher, this being one ofChina’s numerous aid programmes for countries across the African continent. When Ma Ke returned to China in 1999 for reasons that will become clear, he chose to pursue a second period of study under the revered abstract expressionist painter Yuan Yunsheng, who ran Studio Number 4 at the Central Academy of Fine Arts inBeijing. Compounded with his experiences in Africa, this renewed experience of learning—which was one that included a specific focus on classical Chinese painting and culture—shaped a new direction and ambition in Ma Ke’s painting. Although looking back, Ma Ke describes his independent practice as beginning in 1994 when he became a teacher. ‘Since then,’ he explains ‘I have been wholly engrossed in the world of illusions I explore through painting. Painting has made me the person I am today: it is my greatest true passion.’2

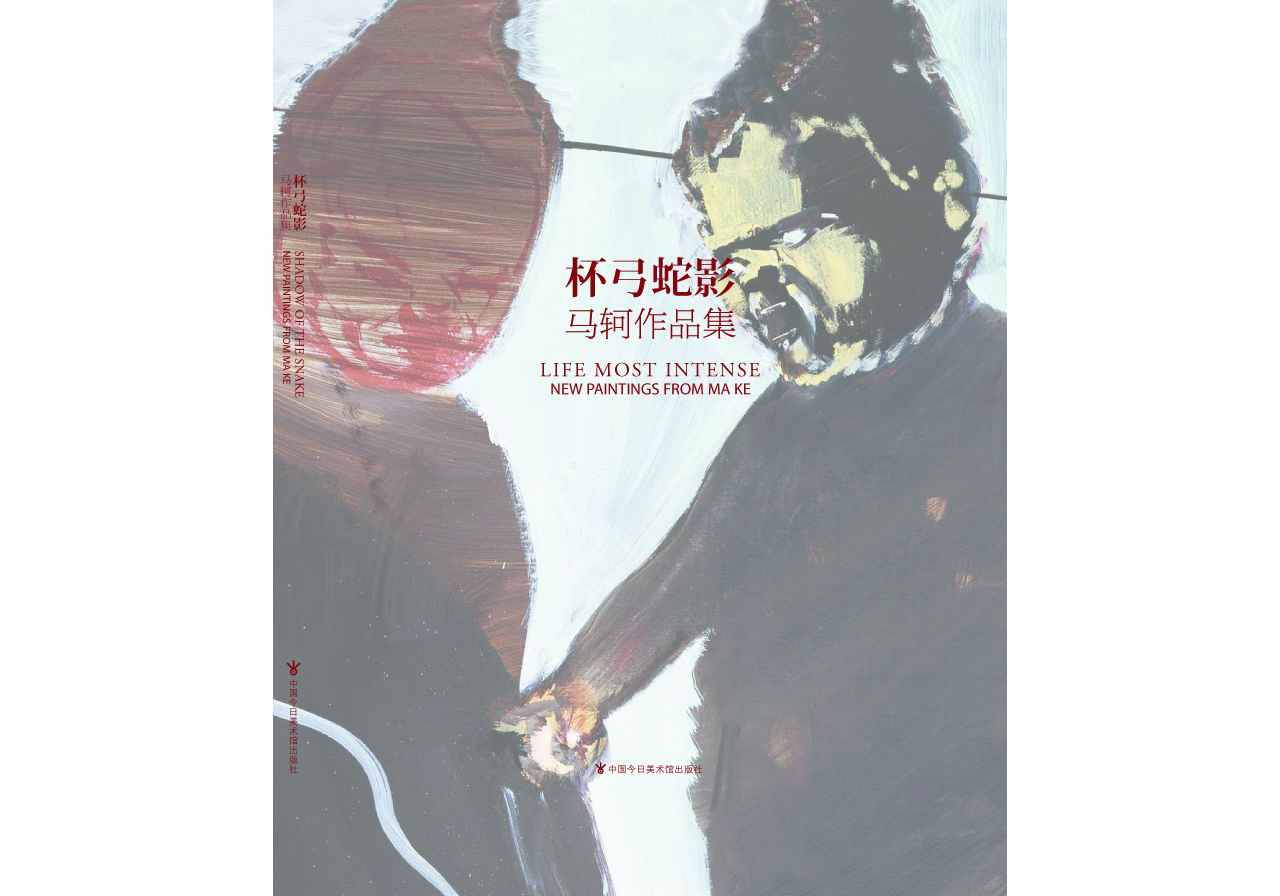

Counting thus, to date Ma Ke has been working at his art for close on two decades. So why might it be, then, that thus far his work is known only within a small circle of friends and collectors? His name is certainly not recognised within broader contemporary art circles in China. That is clearly not due to any lack of ambition for his art, rather that Ma Ke has been so preoccupied with evolving his painting style that he has, to date, given little thought to the task of self-promotion. But there comes a time in every artist’s life, when the need to share their work becomes paramount: a time when conviction begins to outweigh doubt, when clarity occludes confusion, when the very essence that has been sought suddenly falls within reach. At that moment, the art demands a public. And, so here it is: a public presentation of Ma Ke’s painting in a first major solo exhibition titled Life Most Intense.

For anyone who owns a particular appreciation of painting, the exhibition will have been well worth the wait. Ma Ke is a painter in the best possible sense of the word—a sense, that today, is almost oldfashioned. We might even describe Ma Ke as China’s first truly Modernist painter. Although in terms of content and narratives Ma Ke’s style is very much of the moment, in terms of painterly concerns, he paints in the sense that pre-WWII painters in Europe approached the challenges of capturing a changing and troubled world on canvas, and of how they struggled with the language of painting in attempts to break free from the linear trajectory of art history, which appeared to be approaching its end following the total abstraction of the Constructivists, of Kandinsky, Klee and the rise of Duchamp. For a figurative painter in the mid-twentieth century, after Picasso, where was there to go? Even Surrealism might seem like a step backwards in form if not in content. That was a conundrum the British painter Francis Bacon attempted to resolve. The early development of language and style visible in Ma Ke’s paintings prefigures an awareness of pictorial problems Picasso and the Surrealists attempted to resolve, and arrives at a similar conclusion to that embodied by the respond provided by Bacon. In the process of composing a picture, painting as a structural mechanism and linguistic took is given as much consideration as the sociological problems Ma Ke explores. Thus to term Ma Ke a Modernist speaks to his awareness of the evolution of artistic language and the challenges this presents for a painter a century after Picasso, at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

In response to this challenge, Ma Ke looked to Chinese culture and, under guidance from Yuan Yunsheng, devoted several years to an intensive study of pre-Qing dynasty murals and scroll paintings. ‘I felt it was important to understand our profound traditional culture from looking at examples from history: what you see in books doesn’t count.’3

The influence this has had upon his thought processes or visual language might not be immediately obvious in Ma Ke’s paintings, but the experience gained here is very much part of the mindset that informs his approach today, albeit it in subtle ways. This can be found in works such as The Snake’s Shadow , from which the exhibition takes its chinese title. The Snake’s Shadow is typical of Ma Ke’s painting in several ways. It contains a pair of figures engaged in an awkward act of confrontation or exchange. The nature of that exchange derives from a proverb and makes a play of the tale of a man who perceives the reflection of a snake in a shadow, revealing a deeply suspicious mindset that sees danger or subterfuge where there is in fact nothing but the figment of his own imagination. 4 The compositional style here, too, is typical of the angle from which Ma Ke habitually depicts his subject, and the physical distortion to why are, as a result, often subject. Cultural nuances are tied to fundamental human experience in a powerful way and, in Ma Ke’s paintings, in ways that are at times rather disturbing.

A first encounter with any one of Ma Ke’s compositions can indeed be a disquieting experience. Perseverance, however, rewards he viewer with the discovery of multiple details that were previously occluded by the initial impact of the painting. The details are important; they give the paintings the emotional and psychological depth which makes them so distinctive. It is here that the painterly aspects of the work are most clear, and most visually satisfying for the textures and forms they contribute to the painting as a whole. But they also contribute to a realisation thatMa Ke has devoted much time and energy to perfecting what amounts to an aura of the macabre, of veiled horror. Becoming cognizant of this only heightens the fugue of foreboding that emanates from the works; an acrid scent of bitterness that underscores the sorry moral tales each painting is conceived to convey. This paradox of painterly perfection is the root cause of instability in Ma Ke’s painted world.

Surprisingly for a style of painting one might describe as purposefully ugly and on themes that at times appear distasteful, Ma Ke’s style of painting is strangely addictive; in his paintings the ugly, distasteful side of reality and human nature as he presents it is compelling. It is that same compulsion that makes cruelty compelling; that permits sites of disasters and injury such as those immortalised in J. G. Ballard’s Crash to transfix even the most innocent gaze. ‘I always think art has to reflect one’s spirit or oneself from another angle of life.’ Ma Ke explains. ‘The starting point of my paintings is rooted in reality and the experiences of daily living; of surviving daily events. Those which have left the greatest imprint upon me relate to the relationship between people and which are beyond language, indeed beyond all possibility of rational discourse.’ 5 Following this logic, Ma Ke has never worked with photographs as a visual resource for his paintings. This is less about wanting to paint the physical world in a manner that is different from its image as fixed by the camera and more about trying to render the physical world as a spiritual place without relying upon narrative drama to convey this, including the standard Golden Section conventions used to define space on two-dimensions. The paintings are then, the visualisations of the feelings he has when experiencing ‘life most intensely, before routine, time and distance dull the shock and veil the memory.’

Irreconcilable

'The paintings that most haunt us are most often those that hint at their own instability: the unbridgeable distance between technical bravura and the world it ostensibly doubles, even when the illusion is more compelling than the material reality.'6

One of the first of Ma Ke’s paintings I saw was Embrace . This was in his studio in the heatof early summer in 2011. It was not seasonal warmth that made his studio seem so stifling; it was the presence of this painting alone, and was prompted by the fathomless expanse of blackness that appears to be draped over the two figures on the left side of the painting. Juxtaposed with the blackness of that spatial void is a dramatic slab of sanguine brilliance that each of the figures wears as a piece of upper body clothing. It is a contrast with which

another Modernist, Chiam Soutine, would well have been satisfied. The red is a vermillion so living and vital, bulky and yet so flat, that the first impulse was to recoil, to allow the eyes to adjust. The sensation here is slightly different from walking into a dark room and discovering that there are people inside with whom you collide gently and awkwardly with an embarrassed laugh and invisibly reddened cheeks [as was explored by Polish artist Miroslaw Balka with the black box titled How it is in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern in 2010]. At the same time, it is not without its similarities for Ma Ke does force us to stumble into the scene and, in so doing, to confront our own nature as penance: that sensation is awkward and far from being humorous.

What is it we see? That blackness, yes. Such velvet darkness may well be associated with Chinese ink, but ink is rarely deployed in such blanket force as the opaque layers of oil paint that Ma Ke has applied here. This is the kind of charred coal, lamp-oil black from out of which the aging Rembrandt peers in his later self-portraits, at that point in life when he was struggling to stave off the darkest night of all; death, the pitch veil of eternity that approaches with its all-knowing certainty. It is also the terrifying aura of the unknown so beloved of Francisco Goya, as his distinctive use of tenebrous shades of black demonstrates so well.

In Embrace that blackness is but half of a puzzling equation between the two sections of the pictorial space, without which either one might be less intense, less disturbing and rather less irreconcilable than Ma Ke has brilliantly managed to make them. That delicate balance depends as much upon the tension between the two figures on the left themselves as between the physicality of this “couple” and the void that surrounds them. Who are they? A large stolid male figure stands inviolable with his arms wrapped around a woman whose head is ever so slightly inclined to his shoulder. Even though she looks down, her gaze lowered just enough to render her posture ambiguous, her face is revealed to us. It is imperative that we fully grasp her expression: in looking stubbornly downwards, her eyes shield themselves from a full external scrutiny. They are actually closed and, for that reason, it is first instinct perhaps to assume that she is enjoying the embrace: surely, a human being ought to be contented to be thus in the arms of a lover in the solitude of the dark. The darkness, coupled with the sense of intrusion that is fostered on to us, suggests that we have stumbled into a private space and, in so doing, uncovered a stolen, secret clinch between two willing individuals. Yet, at the very same instant, something tells us that this assumption is wrong. Something is not right in this relationship at all. The tension is palpable. The more you look the more the woman seems to be trapped against her will: submitting, because there is no option not to, but hating every single moment of this enforced contact. Her stillness, her silence, speaks volumes. She is like a victim of domestic violence who is unable to speak of her pain other than to herself in secret where there is no one around to hear. So there she is, playing a role, complicit in a charade that she must grin and bear, and endure in silence.

“She” might also represent the ordinary person, the people: “he”, China’s former Chairman, who held the nation, the masses, in a stifling embrace such that almost squeezed the vitality out of them along with all individual volition. The metaphor, if it exists here, is a subtle and a layered one, since the Chairman’s appetite for the female sex is also welldocumented and further encourages this deduction because which one of the objects of this Lothario’s attentions was ever in a position to resist? Thus, the more you look at this painting the more it threatens to destabilise your world through the workings of the very pictorial means that Schama cites for artists like John Constable, Vermeer, Jackson Pollock and Caravaggio. You would not be wrong to ask if that feeling is simply determined by the viewers personal experience alone, in this case mine, rather than being a universal response. Time spent with this or, indeed, with any one of Ma Ke’s paintings definitely provides the answer to that question. Thus, as more opportunities arise to see his works in public exhibitions there will be much to be discussed in this vein. For now, where to another’s eyes it might be a charming exchange of love, to me this embrace seems threatening, cruel even. That is also because I have spent time not just with this painting but looking at all Ma Ke’s paintings. When Embrace is placed in the context of Ma Ke’s broader body of work, softer interpretations become rather untenable. Then, in the approach Ma Ke takes to composing painting after painting, his aim appears solely to unsettle and to destabilise. Embrace is simply one of his finest examples.

In general, what feels most irreconcilable in Ma Ke’s works are the casual expressions of so many of the figures in their juxtaposition with others nearby who seem to be in positions of danger or distress. This is abundantly exampled in earlier paintings dating around 2006-8 and which are, on the whole, much more literary in ambience than those produced in recent years. The scenes are underpinned by a dense drama that has been tightly, intricately constructed. From the positioning of the players, we might be looking at scenes from a farce - a dark play by Bertol Brecht or Jean Genet. Unlike Embrace , many of these compositions appear as if we, as viewers, have interrupted the action; as if everyone on Ma Ke’s “set” has stopped mid-flow following our intrusion into the space and is attempting to present us with some kind of “normal” expression until we pass on out of sight. Caught in the headlights of our gaze, these scenes and the disturbing activities they seem to portray are as moments of naked reality. The tension aroused by the possibilities we imagine here is unnerving. In the stillness we confront, there is no specific point on the anvas to provide unassailable evidence for any specific act, but the general implications are hard to ignore: women are sprawled on the ground surrounded by weirdly grinning men, hands thrust in their pockets as if they are simply hanging out, all the while surrounded by an eerie environs comprised of odd assortments of furniture, household utensils, mechanical implements and construction materials. The more you look the more the possibilities narrow, until all translates into an aura of masochistic violence.

In one such composition, entitled Interior , a woman sits in an easy chair in the pictorial mid-ground, on the left side of the painting. Directly to her right—behind her for now but poised to overtake her—is a woman whose head is haloed by an arc of five knives suspended mid-air. Whether in wielding the knives that action is part of a juggling-act or the advance of an assassin’s blade, we cannot say. The woman’s head is rolled back and she glances to the left with her mouth open. In this posture, she could simply be calling to someone “off stage” and thus invisible in the scene, but there is something about her expression that suggests a maniacal glee. We are directed to this conclusion by the fact that she appears to be closing in on a hapless man who lies face down across the width of the pictorial space in the centre at the bottom—the very front—of the composition. He gazes out towards but not quite at us. We’re momentarily stumped by his demeanour because it is not at all clear what he is doing, and the fact that he is apparently unaware of the woman and the knives looming so threateningly at his back. He also does not seem particularly distressed by the fact that he is weighed down by the enormous black ball that nests in the small of his back. So whilst his being thus pinned down suggests some form of torture or vengeance about to be unleashed, it might simply be part of a game of William Tell; a circus act put on with full melodrama for our entertainment.

The seated woman apparently sees nothing also—as does a second, who stands with her back to all towards the far recesses of the “set” - but we cannot decide if her gaze is turned away innocently or deliberately. This lends an edgy quality to the confusion. It is part of the act? Is the “blindness” of figures like these real, or wilful? Do they exist to represent the complicity of all who live in societies which negate any individual will to stand up and act?

As if to reinforce this point, Ma Ke has created any number of comparable paintings that follow in the same vein. Trial Chair maintains a deep divide between two beings that co-exist in the same temporal-pictorial space. The woman on the left of the composition holds a “head” between two lines that could be a wire, two lengths of string, or some form of “pincer”, scientific measuring instrument or a simple pair of compasses. Ambiguity rules here, particularly in the expression of this modern-day “Judith” [Judith as the “heroine” of the Biblical tale of Judith and Holofernes], although there is little to commend her to the role of heroine. Is this another type of parlour game, where people pass an object between them from one to another using an unusual or unfamiliar implement to impinge upon the fluidity of the exchange to test their motor skills: drop the head and you’re out. This references a similar anxiety of being drawn into an activity perceived to be an innocent game only to discover it to be otherwise. This prompts a second layer of anxiety close to fear, as the person feels obliged to continue to do things they have no wish to do, of which under normal circumstances, they would consider themselves incapable.

The woman on the right of the painting, meanwhile, seems quizzical. Her hands are held—defensively it seems—against her stomach. She wants no part of this “game” we assume: the impassive squint of her expression is surely there to conceal the concern that lies beneath. It is as if she refuses to be consciously complicit, but tacitly accepts the inevitability of what is taking place. Her body language seems to imply that she sees nothing as being within her power to change. A refusal to partake is negated by her inability to walk away. She is thus paralysed. That, then, is the rub; in whatever way or by whatever means you try to account for it, to do nothing is to be complicit. as if she refuses to be consciously complicit, but tacitly accepts the inevitability of what is taking place. Her body language seems to imply that she sees nothing as being within her power to change. A refusal to partake is negated by her inability to walk away. She is thus paralysed. That, then, is the rub; in whatever way or by whatever means you try to account for it, to do nothing is to be complicit.

Much of the tension in Ma Ke’s paintings derives from the distance-proximity and aura of one central figure-actor and the ambivalence of the secondary players that is conveyed here in Trial Chair . It is a tool he uses again and again, as he does similarly with the juxtaposition of anger and coldness, of violence and frigidity, and of the casual attitudes of those who do not see and the imminent anguish of those about to be done unto—as in Interior . Increasingly through the years this has been achieved through a reduction in pictorial elements as the illustrative or literal devices are replaced by shorthand notations. It is often the case that as an artist becomes increasingly comfortable and confident of their style they set in motion a process of reduction and distillation through which early excess gives way to an ever more precise clarity in pictorial preference and vocabulary appropriate to expressing it. As part of the process, every edge, every line and stroke, every mark, is considered, plotted and individually crafted. The sense of dramatic action is no less prevalent in Ma Ke’s recent works, but these are comparatively simple and abstract compositions constructed of limited yet versatile elements. Nothing is left to chance although chance is everywhere in these paintings as a result of what happens when one stroke crashes, collides, or as one colour overlays another, like a code or cipher that is never what it appears to be on the surface.

The elements consistent in Ma Ke’s paintings come in several forms. First is the range of techniques applied to creating physical spaces and to stretching space such that the figures appear to bend through it if caught in transit from one spot to the next. That is the reason why the heads and bodies of Ma Ke’s figures are weirdly foreshortened to appear abnormally squat and thick. This is Matrix [as in the movie] time-space in which odd lines engraved on the surface of the paintings represent both planar borders and divides and, on occasion, bindings, as in the bonds of psychological captivity.

Next, is the dramatic, emphatic use of black, both as a general backdrop to a composition and as a colour. Where used in the background, it is not intended to achieve a superficial visual drama with any other contrasting colour. Instead, it represents the infinite spread of space and time, so far from flattening the space of the picture plane, it creates a hulking void; a changeless eternity as seen in Embrace . Where Ma Ke uses black as a colour—as a solid as opposed to open space—he manages to imbue it with a frightening power. This is most obvious in the shape of the “black” female figure that makes recurrent appearances in scenes that also recur. This recurrence is not merely a repeat of the elements of which a painting is constructed but of the aura of menace with which Ma Ke suffuses them. The “black” woman suggests herself as a man’s worst nightmare. She is as electrifying as Francis Bacon’s Pope [Study after Velasquez’ Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1953 ] that is, if it were not for the fact that she is Victim not Aggressor, for she is consistently portrayed in the act of shrinking back from the foreground under some unaccountable duress or from a concealed cause for horror. Perhaps she merely speaks of the dark side of human nature, as the yin to yang of the male figures that join her in these scenes, but either way, she would not be misnamed as the embodiment of Fear.

Colour is another consistent element of Ma Ke’s paintings. They are inalienably cool in tone; even where a bright hue such as the pink and lilac Ma Ke has a fondness for [as in Love Story of the Empire and Portrait ] is used it is icy cold. There is a recurrent acid yellow, a China red, and a very cold crimson. Some of these colours, the way they are used to produce striking visual contrasts, maybe well result from a period that Ma Ke spent in the newly created nation-state of Eritrea in 1998, as a volunteer teacher, there to train art teachers the name of Sino-African friendship at the nation-state’s one university. He was there alongside the first medical team and

construction crews sent fromChinatoo. With the exception of the newly-built capital,Asmara(meaning “paradise”),Eritreais a small, ancient place where dwellings might easily be several hundred years old. Here light, climate and geographical landscape combined to a visual world quite unlike anything Ma Ke had previously encountered. ‘I lived in a new part of Asmara. The newness of it all felt very strange. There were only two factories atAsmarathen—one shoe factory, the other producing laundry detergent—therefore, it had little pollution. The air was pure, the sky clear. The colour of the land, the people, was very pronounced,’ Ma Ke recalls.7

Unfortunately, there are no examples from that time in existence that could illustrate a direct influence being exerted. Whilst there, Ma Ke produced a few paints, albeit on a necessarily small scale: he shared an apartment with two other teachers and space was tight. But there he had an unfortunate date with Fate. He had only been in Eritrea for a few months—hardly time to settle in—before a border dispute with neighbouring Ethiopia escalated into armed conflict in August 1998, forcing a speedy departure. In the general scramble to leave, as all non-Eritreans were evacuated, the Chinese embassy staff inadvertently abandoned the volunteer workers on secondment there including teachers like Ma Ke. Left to fend for themselves, they were lucky to get out any way they could. Ma Ke found passage on a boat which brought him, after days adrift in the wrong direction, toSaudi Arabiawithout belongings or papers as a “penniless refugee”. It was a memorable experience. ‘In undergoing this frustrating experience [of trying to leave], what struck me the most was the absurdity of the [Chinese] Embassy staff—most of whom could not speak English. The Embassy was a nice, comfortable working environment. The people working there were often relatives. What can be worse? The ambassador was frank but wooden-headed, especially when he talked to the local minister of culture. He did not look like the ambassador for a big country. The system appeared to have tamed him, to have broken his will.’8

“Frank but wooden-headed” is a description that can be applied to any number of the male figures in Ma Ke’s paintings, as indeed, is the notion that a “the system of organisation” tames people such that it breaks their will. Is this what Embrace truly represents, we might ask? The choice of stories Ma Ke invokes in his compositions is an endeavour to express this through painting. Here he turns to an established literary convention of using past examples, here classical moral fables, to point to predicaments of the present. As an example, one of his favourite paintings is Trap which he describes as having ‘a literal meaning of subjecting a person to their own worst fear by being trapped into doing something that they would readily force another to undergo.’ 9 This sentiment is joined by stories that speak of idiocy, or perhaps good intentions minus common sense. As example we have Bull-headed , which expresses the tale of the man who drops his sword into a lake and marks the position where he lost it on the side of the floating boat. The purpose of these elements is to transform the picture plane into a stage. Ma Ke’s figures literally act out his ideas, which is why they habitually face front—if not moving consciously away—and why we always view them upwards as if looking from the audience from the stalls. In part this viewpoint references the heroic vision of role models expostulated in propaganda art produced during the Mao era. Here its use is not intended to present real heroes but as a means of questioning the sapience of fashioning heroes from the flawed beings which most humans are. Ma Ke’s looming actors are utterly human, even as they rise theatrically up in the space to look over the heads of us, the viewers, or, on occasion, to look down on us with uncanny distain and revealing a vulnerability that is all too human, too. This explains their awkward postures; each one embodies a distinct dramatic personae in the manner of Greek tragedy, or mythology. So there is Pathos, here Narcissus. Over there is Spite, Vengeance and, in the corner, Solitude. This link to fate, also in the sense of Greek Tragedy, is a constant undertone of the stories Ma Ke constructs for us to interpret.

Ma Ke learned much about Fate in Africa. The very history of Eritrea, the trials visited upon this tiny ancient place by all manner of extraneous external ambition, was a shocking lesson about the deeds people [individuals as nations] do in the name of geopolitical harmony and stability. Life and death, violence and optimism, pain and loss compounded with determination were ever present in the daily life he witnessed there, and providing another dimension to all that his knowledge of history in China imparted to him. But elements of suffering at the hands of Fate, of events beyond one’s control, run in Ma Ke’s family. Sometimes it just needs an experience to crystallise them into consciousness.

When my grandpa was thirteen years old, he set off on foot from Zibo to Qingdao to seek aid from his father’s elder brother. His father had gambled away the household’s possessions and house, leaving the family destitute. His uncle was a humble street sweeper in Qingdao, but the old man was able to teach my grandfather how to read and write. Not many people were literate at that time, so, with the dream of a better life, my grandpa walked on to Shanghai. There, after years of struggle, he was given the chance to work in a bank. As the civil war was waged, he bought land and built houses. Then, New China was founded and he met his downfall. As a fat man, after Liberation in 1949 the social status of my grandpa was low. To be fat at that time suggested you were rich [a capitalist, he was also a landlord, both of which required he be “overthrown” by the people]. This curtailed my father’s dream going to Shandong College of Arts even though he had been accepted, which made him rather depressed. I think their individual struggle had nothing to do with that era, for they were both simply unlucky.10

Ma Ke was, in this respect, lucky. Although he had to wrestle occasionally with Fate to arrive at his desired path in life, his battles were minor, at least more evenly pitched. In describing him as following the route typical to most oil painters in China, I meant that he found pleasure in drawing at a young age and in painting, too, and, in light of his father’s unrealised aspirations to attend an art school, there was a ready supply of painting materials to hand in the family home. But the experience of his father was then projected onto the son. ‘I wanted to paint more than anything,’ Ma Ke recalls ‘but my father did not encourage my wish to study art. So although I was a good student in general, I gradually began to rebel. I didn’t want to be like those obedient students who were good at learning. There was a period of time during my junior high school days when every Sunday I rode twenty kilometres to watch people drawing. When my mother found out I had to stop.’ It was enough to convince his father of the seriousness of Ma Ke’s wish. He finally consented to let Ma Ke study painting, and found a high school art class for him to attend. Two years later, Ma Ke was admitted to Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts.11

Violence and Despair

"Something is leaking into the borderland between the human and inhuman worlds, something not reassuring."12

Ma Ke’s stay in Africa was thus a major experience in his life: not just because he gained experience of another place. ‘It allowed me understand both Africa and Asia to a higher degree for the broader perspective it provided on different places. For instance, I had previously thought of Europe as a place of rationality and logic; of Africa as a place of human zeal and primitive essence; and of South America as the home of the surreal. But when I arrived in Africa, I was amazed to discover how surreal it was. Before I left China I had seen an exhibition of Surrealism in Beijing. In Eritrea, it seemed that every element could be traced back to African cultural emblems, beyond the standard attributions of what inspired Picasso or the German Expressionists. From the perspective of Africa, Asian culture was made to seem far more delicate in substance.13

It was the human side of the experience as much as the culture which made a particular impact. ‘I was stuck by a physical difference, for example, how music is embedded in the spirit of Africa. When people hear music every single cell of their body seems to dance; every fibre of their being vibrates to a mysterious melody. On the contrary, Chinese find it unnatural to swing forward and backward to a rhythm, which leads them to think that dancing Africans are bewitched. African people are also relatively straightforward. By contrast, Chinese, most Asian people actually, are more circumlocutionary, perhaps because they are hemmed in by social dogma.’14

One means of expressing this rigidity of his countrymen or of indicating the invisible socio-cultural bonds which hold them captive, is found in the motif of the “muffler” which engulfs the hands of many of Ma Ke’s figures. It is an ambiguous motif: an ill-defined large round object that might be a binding as much as a black hole into which both hands of whichever figure is holding it are plunged. We understand that the hands are not placed there for warmth. Mostly they are constrained as if handcuffed, although occasionally they are concealed as if engaged in an act of duplicity or subversion. The muffler could then be the symbol of a search, but it is a blind search for a means to break free of the society that has these hands tied—groping for stones to cross the next branch of the river of modernisation into civil society? As an object, it is always something with which the figure struggles. In this sense, it also the burdenrock of which the incumbent can never break free; a Sisyphean symbol of unending struggle.

One of two powerful works in this vein, entitled Space , depicts a woman with her hands locked in a muffler as she stares transfixed at the disembodied head of a wolf at eye-level in the space before her. The wolf, which initially could be mistaken for the kind of cat represented in Egyptian hieroglyphs, references a story about deception. In this light, we are not wrong to read the muffler as an image of social control. At first glance, a line distending the space near her feet infers that she is balanced on a tightrope; paused, unable to move forward because the wolf has caught her off guard and arrested her progress. Of course, that line is not a tightrope but represents an angle of space, a measure of floor as distinct from the wall. Is this woman then backed into a corner? Then again, she seems less scared than curious. The minimalism of the strokes brought to cementing her volume in the space, and to imbuing that wolf with a certain supernatural aura, is exemplary. The colour is pale: the milky tawny-apricot of the background against the pinkish reds of the woman and the wolf unite in sanguine breath of conflicted life.

A second painting, entitled Girl , is more disturbing. Her attitude could be one of shock or horror, frustration or anguish. Hunched forward, her hands muffled and, we presume, further united by the lengths of taut black strips of some unnameable material that is attached top and bottom to the mufflershe can it seems turn neither left nor right for she is caught in bind like a self-tightening noose that responds to the slightest motion; tightening, tightening… Incongruous here is the contrast between the raw human essence she exudes and the implied sophistication or sexuality of the cocktail dress she wears. Her figure is cinched at the waist to accentuate both her cleavage and the hunch of her back, both of which serve as a veiled reference to Bacon’s howling Pope Innocent X. The detail of the curved hem line at the front which reveals knees is minor yet deliberate, conscious. Why was that detail so important to Ma Ka, we wonder? The background is pale in tonality, a milky opal, cement grey like semi-dried winter mud. It has been whipped around the pictorial space to find its place, and traces of its passage from top to bottom remain. Out of this implied chaos or place of elemental disturbance, this woman emerges with only what she has witnessed to sustain the energy she now focuses in her hands. We must surely interpret this as a will to escape; what it was that she witnessed, or what force has laid siege to her being, we will never know. What we are left to—forced to—imagine brings no comfort at all.

Pain and Love

'It's in the neighbourhood of imperfectly described things or even in the shifting spaces between them, in the half-tones and the gracenotes, in the slightly unstable location of the subject in the pictorial space that the strongest challenge of art often resides. And it is when the description of objects hints at something other than there mere material constitution, much less their function, that the sorcery of paintings begins. '15

At what point does the sorcery in Ma Ke’s painting begin, for it is surely that which accounts for the darkness that is to be found there. Ma Ke himself is a rather wellrounded character with little of the angst that saturates his paintings. I mention this because in the example of other artists, such as Francis Bacon, being known to be depressive is one explanation writers and critics invoke in accounting for the tortured vision that many number of his great works contain. A similar vision is discernable in as many of Ma Ke’s paintings. But as a reminder of the dangers of equating a presumed psychological state of an artist with their work, Bacon himself once said ‘[people] naturally think that painting is an expression of the artist's mood. But it rarely is. Very often he may be in greatest despair and be painting his happiest paintings.’ This seems to be true of Ma Ke’s paintings, too, for his personality clearly evades a direct alignment with the content, the narrative viewed in his compositions.

Like Bacon, Ma Ke wrestles with issues which are not exactly his own demons: yet, some level of angst clearly possesses him profoundly. Watching Ma Ke explaining his work standing before a painting, it becomes clear how profoundly every single one of the figures in his compositions, female as much as male, is himself as much as being aspects of human nature. Generally speaking, his paintings deal with the alienation of the individual in a collective, unified society, but the summation of these observations is transformed into an essence of human experience not limited by culture or by specific events. Individual human problems, however, are often petty. The issues in Ma Ke’s works clearly point to extremes beyond anything the average person might experience, but that does not mean we cannot identify with them. It is often our fear of crossing the manageable thresholds we erect to protect ourselves that is the reason we find the paintings destabilising. That fear, or anxiety as Ma Ke likes to call it, resonates in the “shifting spaces” between the “imperfectly described things” he presents: imperfect because life is never perfect, yet our unstinting focus upon attaining perfection engenders all manner of perverse imperfection of our own making.

The paintings destabilise in the manner Schama describes because they go straight to the point: to the pain of human interaction and how calculated an investment it is for many people. Ma Ke’s Open Sky is a good example. A man occupies the centre stage here, with a woman awkwardly hovering slightly behind him to his right. He is typically statuesque and looks up and out, but not to us for his eyes travel beyond— perhaps into that open sky. He seems to be consciously avoiding the woman, who looks at meanwhile him with an expression that is by no means clear. Is it adoring? Or is it anguished? Her hands in an involuntary clutch speak more than her eyes, for in that action they have gathered up the fabric of her skirt and kneaded it into a knot in her fists. This raising of the hemline, which flashes an inch of flesh, is not intended to beguile. That her legs appear to be firmly gripped together implies great discomfort more than resistance. Is she afraid he will leave? Or that he will stay? Or is it that she been made to feel useless, superfluous? These suggestions may, of course, be completely wrong. Instead, this woman may be in the grip of nothing more than terminal boredom and aches for the moment when he, the self-absorbed, egotist will exeunt and leave her alone and in peace. If waiting, then her expression is simply one of enforced silence as she bides her time. But as we consider this, we may well decide that her posture is the external shape of an internal dilemma; an involuntary sense of complicity in her knowledge of whatever it is he is about to do, or whatever it is that he might have already done to render her being to visibly ill-at-ease. Whatever the answer, the important point is that Ma Ke has got us thinking and created myriad paths for our thoughts to pursue. As they do, we find he has created a mechanism for exchange and communication all too rare in today’s experience of art. Whatever else we may decide, Ma Ke’s “actors” are read as threatening beings, or as embodying threatening human traits. He seems to appreciate the human potential for greatness and society’s need for role models, if not the kind that are upheld to be so in his nation. He is not so specific as to speak of things Chinese alone; via those stock characters, he transcends the expansive borders of his culture to arrive at a universal human essence.

Betrayal is the single most dominant emotion in these dramas. There are no allies in Ma Ke’s world. Everyone is to be distrusted, and is distrusting of those with whom they are forced to share the painted stage. The story of Judith and Holofernes is just such a tale of deception and betrayal that leads to the death of one deceived. This tale as related in the Bible is an example of the oppressed vanquishing the oppressor; virtue conquering vice using the kind of strategy articulated in Sunzi’s Art of War . As with any piece of history, examined from another place and time, we might well question its moral certitude in the light of less exacting historical circumstances. We might see such historic tales as merely powerful pieces of propaganda. A quick review of The Snake’s Shadow confirms this point.

Ma Ke often compounds treachery with humiliation, presenting one as the inescapable result of the other. Perhaps the figures' awkwardness derives from an innate awareness that if they move, if they turn their back, they might be betrayed; stabbed, Et tu Bruté ?16 We enjoin these states in the paintings the instant immediately preceding or following the act that makes them manifest. Ma Ke never has need of illustrating the act itself. We instinctually add up the clues he provides to arrive at the intended emotional sum. It is this conflagration and the structure within which they are presented and are balanced that sets up a mood of instability in the paintings.

Woman

There appears to be a great deal of sexual innuendo within Ma Ke’s imagery, but none of it sexy. Its degree of violence is matched between the sexes and between facial expressions and bodily gestures. Listening to Ma Ke talk about his impressions of Africa, the casual nature of sexual conquests, the fact of the AIDS plague, and the early age of promiscuity amongst women as compared with China-where he saw women offer themselves to men as if, in his own words, they were ‘ripe dates on a platter’-all left indelible marks upon him. I say this because, in many ways, Ma Ke’s single figure compositions of women are the strangest amongst all the “series” within his body of works. They are almost as a plea for innocence in a corrupting world. They are the simplest in form, all very pure in colour. The women are humble, innocent and unassuming. They are also expressionless to but they are rooted in the earth by feet that plunge off the bottom of the canvas. Where space is given some element of definition, as in Youth 1 , Ma Ke includes odd details like the handbag which suggests an appointment, a journey, and now arrival. The garments in which he clothes these subjects are uniform: practical and economical in style, but the occasional shorter skirt lengths hints at an otherness about the women. The men are, by comparison, more pedestrian in their dress. It makes Youth a curious title; these are the figures of women not girls even though they appear ageless. The question remains why they seem so isolated, so lost?

We see this ambiguity not only in the paintings of single figures of women but also where they appear together with men, as in the disembodied woman’s head held between “pincers” in doll . The division between these two subjects here is, however, ambiguous. The male “puppeteer” looks up into the air above our heads almost dreamily, whilst in his right hand he holds, slightly away from his body, the disembodied head. Her eyes cast demurely down, she is like a precious doll, a plaything, a pet that is kept on a leash until required, or remembered. Is this Holofenes revenge-is it Judith’s head because Judith’s act was deemed to have upset the natural order of dictatorial power which could not be permitted to prevail without a reversal of that act? So should we read the male and female roles in terms of yin and yang, then, as the weak and the strong; as the ruler and the subject?

Stories

'At times, it is not easy for me to create as I have no fixed method or process in my work. I have to have a story or the painting becomes a game.' 17

Reading this statement we assume that Ma Ke’s paintings must all relate to a story of one kind or another. Whether familiar cultural tale or proverb, the stories often have a moral purpose, which Ma Ke unravels and, occasionally, subverts. In the final paintings, however, any aspect of plot is irrelevant. The stories function as atmosphere; it is without doubt this atmosphere across which the tension is strung for the story provides the framework for mapping out a composition and, equally, for resisting the nature of the game he references. The story is the reason why the figure in the boat is there as in Bull-headed ; why a wavering line runs down a man’s sleeve and why a second male figure feels impelled to point it out as in The Snake’s Shadow. It is the logic that impels the sobriety of the palette, the precise placing and form of the lines. It explains why the entire dynamic of a painting is just so, and marks the end point of the process, beyond which any single line or drip of paint would be like painting feet on a snake.

Where the stories are specific, they do serve to remind us how quick we are to moralise and how easily the moral ground is turned into a vantage point from which others can be ridiculed. In this context, The Snake’s Shadow is a Ma Ke’s fine expressions of human doubt and insensitivity. It contains all the elements familiar to his visual lexicon: two awkward figures of stolid form, in postures that imply a bully bearing down on a victim who brandishes that awful accusing finger. All pictorial elements conspire to hint at the unsavoury nature of fear that bolsters suspicion of others. Ma Ke’s favourite example is Waiting 2 . ‘Everyone in the world is waiting because everything changes,’18 he says. Waiting 2 is his response to the idea that tomorrow will be better.

Yet, beyond all else Ma Ke’s works are still about painting: about what happens on a canvas from the action that imprints the first mark, how the process of creating a scene unfolds, how space takes shape, and how everything within the picture plane is subject to the shifting needs of visual relations such that changes may occur that are as dramatic as the drama they describe. ‘My paintings can seem relatively careless and sloppy at times,’ he says ‘without any consideration of formal pictorial problems.’ And yet, evidence of the process of considering what goes where is everywhere in evidence in the traces of multiple changes which echo in the final work, their shadows trapped in layers of semi-opaque paint as they are built up. These are age-old concerns and values, which are accorded supporting rather than leading roles in contemporary art, here take a starring role.

To engage with painting today is challenging. Where once Chinese painters looked to the West for inspiration, against the vibrant, pluralistic scene that exists in China today that need is no longer there. Today, the entire world is struggling to find something new as artists ask not just what is painting, but what is art? Again, in responding to this question, it is Ma Ke’s study of classical Chinese culture, which continues to inspire. ‘I paint slowly and intuitively. I am not focused on one problem. I frequently jump from one point to another. For my generation, the concept of painting has yet to crystallise. I am always asking myself what is painting? What is my painting ?’19

Landscape

Whatever its position within the contemporary artistic canon, painting remains an essential part of any nation’s cultural life and of the individual’s daily experience. ‘A fine piece of art makes my day brighter and nicer. It lifts my mental state,’ Ma Ke states. ‘We need to illustrate our existence by virtue of our brain and creativity. In doing these things, we may become aware of our own individuality or creative expression. In the transition from traditional culture to a new one [as in the present time], Chinese painters ought to create a brand-new style and form and spiritual freedom. Within a new style of art development, such as traditional Chinese painting, it will be good for nothing if its spiritual resource is from ancient time and does not resonate with its times.’20

Ma Ke’s work with contemporary urban landscapes is an attempt to do just this. There are bulldozers and fallen telegraph poles (girders?), derailed train carriages and monolithic flyovers and concrete tunnels. There is heavy machinery, cement trucks, bulldozers and workmen. Sandstorms whip across open land, turning all to ochre dust in their path, while deep purply-black tornados emerge from the depths of dark nights to unleash havoc in their wake, hence the train crashes and similar spread of debris. This is the imprint of urban redevelopment impinging upon Ma Ke’s world view, and forcing itself a role in his art.

Some compositions, as for example the painting titled Accident in the Night , were inspired by real events. ‘In 2008, there was a car accident in Zibo, and quite a few people died. In the painting, I left the space open as in a traditional Chinese painting. It is different from a scene captured by a camera; the space twists and yet appears flat at the same time. Here I succeeded in creating space within a painting.’21 In Chinese painting, an object exists such that the viewer identify with it. If a tree, then the viewer associates with its “treeness”, not a specific individual tree. The object creates a point vis-à-vis any other object in the painting, and becomes a marker of the This last point denotes an important characteristic within Ma Ke’s approach and that shapes the goals he aims to realise in his paintings: that is how Western-style oil paintings relate directly to local cultural concerns. space. The position of the object in relations to others is not about “distance” in the physical sense. It is not an attempt to signify perspective in the western, scientifically measured manner but via metaphysical implication. The eyes scan and the brain fills in the blanks. ‘Every painting has to resolve space, physical or pictorial. I can still remember how shocked I felt the first time I saw a four-metre high mural painting in a Tang Dynasty tomb chamber. The grand and magnificent power would make you think no other painting in the world can be better than this. Through all my experience, I realise that to paint surroundings or environs does not add anything of import to the drama or narrative which a figure is conceived to embody.’22

In his approach to painting an idea by returning to it again and again, we might decide Ma Ke has something of an underlying Sisyphus complex. Delacroix is quoted as saying ‘What moves those of genius, what inspires their work is not new ideas, but their obsession with the idea that what has already been said is still not enough.’ Ma Ke agrees that in his eyes there is so much more to be mined from the subjects he has begun to explore. Where he is heir to a culture shaped by several long decades of socio-political and cultural propaganda, the concept of the individual and the space within which it is able to explore what individuality might mean offers Ma Ke much to reflect upon. As this new form of existence is buffeted by the contemporary world, by economic pressures and by the challenge of surmounting social obstacles, so the nature of individual being takes on a profound new ideological significance in China. In Ma Ke’s hands, Man’s potential is transformed into a conundrum, a dilemma to be resolved. His visualisations of human interaction are given a bitter rather than an ironic—cynical—twist as they were by the generation of China’s independent artists to emerge in the early 1990s. China had made tremendous advances since then and the questions is it now possible to ask can be answered in ever more complex and meaningful ways, right here within society; no longer the purview of those on the outside looking in. For Ma Ke, this exploration can be achieved in a really meaningful way through painting, which alone feeds that ‘unassuageable craving to nail down transient experience’, through illusions that are ‘more compelling than the material reality.’23

1 Simon Schama, “Introduction”, Hang-ups: Essays on Painting (Mostly) , BBC Books, UK, 2007, p.9

2 Interview with Ma Ke, December 2011

3 Ibid

4 During the Han Dynasty (206BC-220AD), there was a county magistrate called Ying Bin. One summer day, he invited his secretary Du Xuan to his house and treated him with wine. On the north wall of the room hung a red bow. It was reflected in Du Xuan's cup. Du Xuan took the reflection for a squirming snake. He was very frightened but he dared not turn down Ying Bin's offer because he was his superior. He had to swallow the wine with his eyes closed. When he was back at home he felt so painful in his chest and stomach that he could hardly eat and drink any more. He sent for the doctor and tried much medicine but nothing could cure him. When Ying Bin asked Du Xuan how he got so seriously ill, Du told him he drank the wine with a snake in his cup the other day. Ying Bin found something strange about that. He turned home, thought hard, but he couldn't find an answer. Suddenly the bow on the north wall caught his eye. ‘That's it!’ he shouted. He immediately sent his man to fetch Du Xuan. He seated him where he sat before and offered him a cup of wine. Du Xuan saw the snake-like shadow again. Before Du was scared out of his wits again, Ying Bin said, pointing at the shadow, ‘The “snake” in the cup is nothing but a reflection of the bow on the north wall!’ Now that Du Xuan knew what it was, he felt much easier. His illness disappeared the next moment! This story was later contracted into the idiom mistake the reflection of a bow in the cup for a snake. It is used to describe someone who is very suspicious.

5 Interview with Ma Ke, December 2011

6 Simon Schama, “Introduction”, Hang-ups: Essays on Painting (Mostly) , BBC Books, UK, 2007, p.10

7 Interview with Ma Ke, December 2011.

8 Ibid.

9 In the reign of the Tang Dynasty Empress Wu Zetian (624-705), there were two tyrannous officials named Zhou Xing and Lai Junchen, who were ingenious at inventing cruel tortures. When Zhou Xing was accused of plotting a rebellion, Wu Zetian instructed Lai Junchen to arrest him. Lai Junchen invited Zhou Xing to a banquet, during which he asked him what was the best method of making a prisoner admit a crime. Zhou Xing said that the best method was to heat an iron vat red-hot, and then put the prisoner in it. Thereupon, Lai Junchen ordered a vat to be heated. When this was done, he said to Zhou Xing, "You are accused of plotting a rebellion, so please get into the vat." Zhou Xing immediately admitted his guilt.

10 Interview with Ma Ke, December 2011.

11 Ibid.

12 Simon Schama, “Introduction”, Hang-ups: Essays on Painting (Mostly) , BBC Books, UK, 2007, p.18

13 Interview with Ma Ke, December 2011.

14 Ibid.

15 Simon Schama, “Introduction”, Hang-ups: Essays on Painting (Mostly) , BBC Books, UK, 2007, p.12

16 This is a quotation from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar , which Caesar utters when he is betrayed by his most loyal general, Brutus, who stabs him in the back having been persuaded by disloyal ministers of the need to replace Caesar by force.

17 Interview with Ma Ke, December 2011.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Interview with Ma Ke, December 2011.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Simon Schama, “Introduction”, Hang-ups: Essays on Painting (Mostly ), BBC Books, UK, 2007, p.10